Subscribe to stay informed, inspired and involved.

Sign up with your email

chevron_right

The Board and Stakeholder Engagement

If you read these articles regularly you may have spotted that there tends to be a recurring theme, which is the increase in the duties and workload of directors and the expectations placed on them by regulators, investors and others. Boards have to prioritize and find ways to ensure that they are spending most of their time on the most material issues.

But even identifying what those issues are is more complex. The days when you could just assess the impact on the bottom line are long gone. Boards now need to think about what is called ‘double materiality’, defined as including “topics that have a direct or indirect impact on an organization's ability to create, preserve or erode economic, environmental and social value for itself, its stakeholders and society at large .” [Reference: Definition from the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI)]

One way of prioritizing issues is to look at them through a stakeholder lens, but even that is not straightforward. Most companies will have a multitude of stakeholders whose interests will often conflict, and each of them may interact with the company in multiple different ways. Again, there is a need to prioritize and assess which stakeholders’ interests are material.

Broadly speaking, stakeholders can be put into one or both of two categories. The first category regards those whose inputs the company relies upon to be able to run the business successfully, such as the workforce, investors and suppliers. The second category is for those whose support a company requires to retain its ‘license to operate’ – the same as previously – but also customers, regulators and the court of public opinion.

Stakeholder Management Considerations

The contribution of the first category of stakeholders is clearly critical to delivering the strategy, and the views of the second are equally important to managing the significant risks facing the company. So the strategy and the risk register should be the starting point for identifying key stakeholders.

At the same time, the materiality matrix strategy and risk register themselves need to be informed by the views of, and an understanding of the impact on, those same stakeholders. It is not a one-way relationship. Boards alone don’t get to decide what is important.

There have always been many examples of where failure to anticipate the impact on and opinions of certain stakeholders resulted in damage to a company’s performance or reputation. We are increasingly seeing examples of where a company’s agenda is being set by stakeholders, not the board – for example, by regulators and investors in the case of climate change.

This is why stakeholder management needs to be viewed as an integral part of strategy development and risk management, and not just as a glorified PR exercise. Additionally, it is why the board needs to take an active role to ensure that stakeholder interests have been thoroughly mapped and approve of the management’s overall plan for stakeholder engagement.

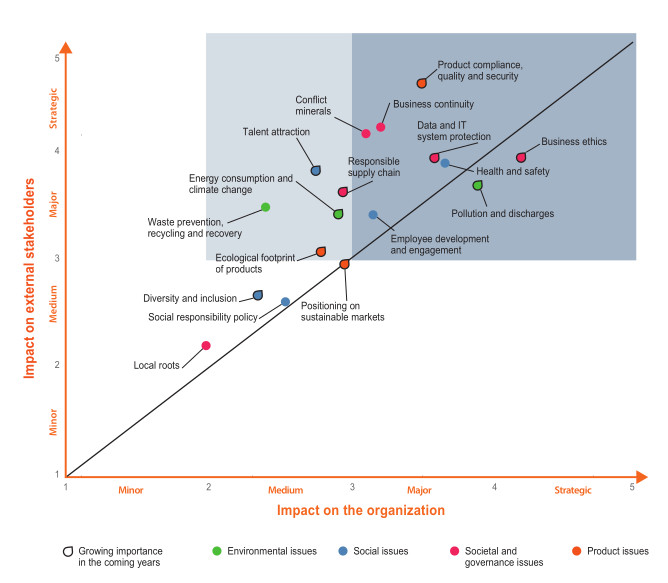

Many companies now use a materiality matrix to help identify the most important issues. They take different forms but essentially what these matrices do is identify and weigh the issues that matter most to a company’s stakeholders and then place them alongside its strategic priorities and key risks. Issues that score highly on both counts are clearly critical.

An interesting example of a materiality matrix is the one used by Mersen, the French electrical power and advanced materials group, which not only maps the key issues but also indicates which ones the company expects to become more significant in the future.

Done well, a materiality matrix can be a foundation stone for strategy development and risk management, as well as stakeholder management. However, it has limitations.

What is a Materiality Matrix?

A typical materiality matrix does not show the relationship between each of the issues identified and the different groups of stakeholders. Each group will have different views on the relative priority of the material issues, and their ability to contribute to addressing those issues will also vary considerably.

For those reasons, companies need to take a more granular approach to understand the views of different stakeholder groups.

This is easier to do with some stakeholder groups than others. Regulators usually make their agenda clear, and companies can engage directly with their workforce. The views of investors can be gathered either through engagement or by drawing on resources such as Morrow Sodali’s annual Institutional Investors Survey.

For other stakeholders, for example, customers and local communities, companies may need to think more imaginatively about how to engage effectively. In next month’s article, we will look at some of the practicalities of stakeholder engagement.

If you read these articles regularly you may have spotted that there tends to be a recurring theme, which is the increase in the duties and workload of directors and the expectations placed on them by regulators, investors and others. Boards have to prioritize and find ways to ensure that they are spending most of their time on the most material issues.

But even identifying what those issues are is more complex. The days when you could just assess the impact on the bottom line are long gone. Boards now need to think about what is called ‘double materiality’, defined as including “topics that have a direct or indirect impact on an organization's ability to create, preserve or erode economic, environmental and social value for itself, its stakeholders and society at large .” [Reference: Definition from the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI)]

One way of prioritizing issues is to look at them through a stakeholder lens, but even that is not straightforward. Most companies will have a multitude of stakeholders whose interests will often conflict, and each of them may interact with the company in multiple different ways. Again, there is a need to prioritize and assess which stakeholders’ interests are material.

Broadly speaking, stakeholders can be put into one or both of two categories. The first category regards those whose inputs the company relies upon to be able to run the business successfully, such as the workforce, investors and suppliers. The second category is for those whose support a company requires to retain its ‘license to operate’ – the same as previously – but also customers, regulators and the court of public opinion.

Stakeholder Management Considerations

The contribution of the first category of stakeholders is clearly critical to delivering the strategy, and the views of the second are equally important to managing the significant risks facing the company. So the strategy and the risk register should be the starting point for identifying key stakeholders.

At the same time, the materiality matrix strategy and risk register themselves need to be informed by the views of, and an understanding of the impact on, those same stakeholders. It is not a one-way relationship. Boards alone don’t get to decide what is important.

There have always been many examples of where failure to anticipate the impact on and opinions of certain stakeholders resulted in damage to a company’s performance or reputation. We are increasingly seeing examples of where a company’s agenda is being set by stakeholders, not the board – for example, by regulators and investors in the case of climate change.

This is why stakeholder management needs to be viewed as an integral part of strategy development and risk management, and not just as a glorified PR exercise. Additionally, it is why the board needs to take an active role to ensure that stakeholder interests have been thoroughly mapped and approve of the management’s overall plan for stakeholder engagement.

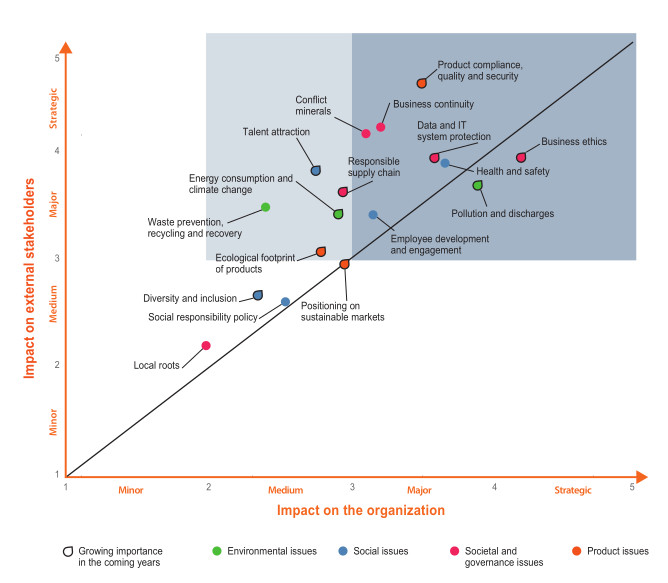

Many companies now use a materiality matrix to help identify the most important issues. They take different forms but essentially what these matrices do is identify and weigh the issues that matter most to a company’s stakeholders and then place them alongside its strategic priorities and key risks. Issues that score highly on both counts are clearly critical.

An interesting example of a materiality matrix is the one used by Mersen, the French electrical power and advanced materials group, which not only maps the key issues but also indicates which ones the company expects to become more significant in the future.

Done well, a materiality matrix can be a foundation stone for strategy development and risk management, as well as stakeholder management. However, it has limitations.

What is a Materiality Matrix?

A typical materiality matrix does not show the relationship between each of the issues identified and the different groups of stakeholders. Each group will have different views on the relative priority of the material issues, and their ability to contribute to addressing those issues will also vary considerably.

For those reasons, companies need to take a more granular approach to understand the views of different stakeholder groups.

This is easier to do with some stakeholder groups than others. Regulators usually make their agenda clear, and companies can engage directly with their workforce. The views of investors can be gathered either through engagement or by drawing on resources such as Morrow Sodali’s annual Institutional Investors Survey.

For other stakeholders, for example, customers and local communities, companies may need to think more imaginatively about how to engage effectively. In next month’s article, we will look at some of the practicalities of stakeholder engagement.

Summary

A materiality matrix can be a foundation stone for strategy development and risk management. Learn why many companies now use a materiality matrix.

Author

Chris Hodge

Special Advisor

London

chris.hodge@sodali.com